"And so I am very pleased that this afternoon that we have completed the biggest trade deal yet, worth £660 billion.

A comprehensive Canada style free trade deal between the U.K. and the EU, a deal that will protect jobs across this country.

A deal that will allow U.K. goods and components to be sold without tariffs and without quotas in the EU market."

— Boris Johnson's statement on EU negotiations 24 December 2020

Although the dark clouds of a no-deal scenario have almost disappeared (the EU countries still need to approve the deal), for U.K. businesses trading with the EU, the skies are not as bright as many had hoped. Again, the devil is in the details. For instance, what is actually meant by the "U.K. goods" reference in Johnson’s statement? Only qualified goods can benefit from non-duty trade with the EU. And this is where the Rules of Origin kick in.

Rules of Origin determine in which country a product was sourced or made. These rules help to ensure lower or no duties are applied where appropriate. For goods to qualify as "U.K. goods," the products must be:

- Wholly obtained in the U.K. (mostly live animals and agricultural products);

- Produced in the U.K. exclusively from materials with a U.K. origin; or

- Made in the U.K. incorporating materials with a non-U.K. origin provided they satisfy specific rules (product-specific rules of origin).

The first category consists of mineral products extracted from the U.K.'s soil or seabed, under a license, or plants and vegetables grown or harvested in the U.K. It also includes live animals born and raised in the U.K. and products obtained from these animals, as well as products of sea fishing by U.K. vessels.

The second category is products consisting only of materials described in the first category.

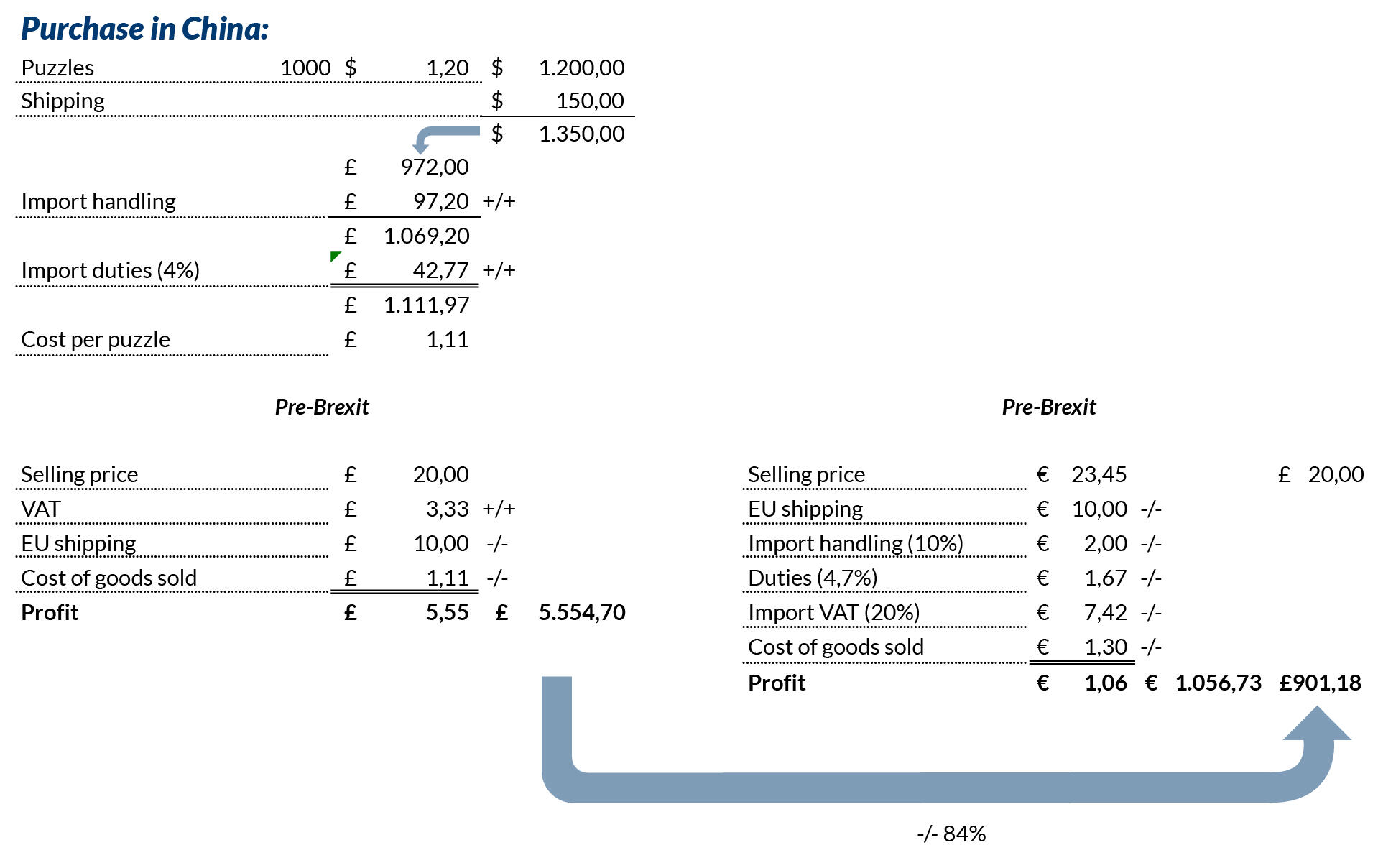

The third group of products is where the main complications lie, and it’s the one currently causing disruptions. Let me explain: Many businesses purchase goods produced in China, import those into the U.K., and then sell to both U.K. and EU customers. As these goods have a Chinese origin, import duties are due upon importation into the U.K. If these goods are dispatched to EU customers, the origin nation is still China. As a result, the EU-U.K. trade agreement's duty exemption cannot be applied, and EU import duties are due. Before Brexit, import duties were only levied once. The drop in profit for vendors can be significant, which is displayed in the below simplified case.

When production activities take place in the U.K., the determination of origin can get quite complicated. Here’s a simplified example: If you produce preserves from strawberries grown and harvested in the U.K., it has a U.K. origin, as that is where the strawberries were grown. However, if you add sugar to make the jelly, the amount and source of the sugar may influence the origin of the end-product. Complying with these rules is notoriously complicated. For some merchants, accepting customs duties may be easier and cheaper than trying to comply with these complex rules of origin.

As a result of these surfaced origin issues, many vendors are rethinking their supply chain and funneling their EU sales directly through an EU entity. But for smaller e-commerce retailers, this may not be a viable solution, and they may be either forced to focus on U.K. sales only or use an EU marketplace fulfillment model to help alleviate the tax compliance burden.